HISTORY AND ORIGIN OF MURGH MUSALLAM

Many of us love ordering the rich, spice-infused, exotic whole chicken (Murgh Musallam) from the menus of sub-continental restaurants. It is a specialty that even seasoned chefs take years to master to perfection. But while enjoying the succulently intoxicating dish, have you ever wondered about its origin, its development over the course of time and the regal history behind this recipe?

As the name itself is self-explanatory, Murgh means Chicken and Musallam means whole. Hailing from the Mughal era, it is a magnificent mouth-watering delicacy that is masala-marinated in ginger-garlic paste, red chillies, curd and other fried spices including saffron, five spice, poppy seeds etc. It is then stuffed with minced meat and boiled eggs, before being slow cooked and served with a garnish of almonds, pistachios and silver leaves.

Murgh Musallam was a widely popular dish during the Mughal regime. The dish is historic in t

Many of us love ordering the rich, spice-infused, exotic whole chicken (Murgh Musallam) from the menus of sub-continental restaurants. It is a specialty that even seasoned chefs take years to master to perfection. But while enjoying the succulently intoxicating dish, have you ever wondered about its origin, its development over the course of time and the regal history behind this recipe?

As the name itself is self-explanatory, Murgh means Chicken and Musallam means whole. Hailing from the Mughal era, it is a magnificent mouth-watering delicacy that is masala-marinated in ginger-garlic paste, red chillies, curd and other fried spices including saffron, five spice, poppy seeds etc. It is then stuffed with minced meat and boiled eggs, before being slow cooked and served with a garnish of almonds, pistachios and silver leaves.

Murgh Musallam was a widely popular dish during the Mughal regime. The dish is historic in the sense that even Ibn Battuta mentioned it to be the favorite dish of Sultan Muhammad Bin Tughlaq. As described in the Ain-i-Akbari, Musamman was one of the 30 dishes essentially present on the Mughal Emperor’s table, which probably was a forerunner version of Murgh Musallam. A German orientalist Heinrich Biochmann translated Ain-i-Akbari, describing Musamman as:

“They take all the bones out of a fowl through the neck, the fowl remaining whole; .5 s. minced meat; .5 s. ghee; 5 eggs; .25 s. onions; 10 m. coriander; 10 m. fresh ginger; 5 m. salt; 3 m. round pepper; .5 m. saffron, it is prepared as the preceding (kababs)" (One ‘s’ (ser) is roughly 900g and 1 ‘m’ (misqal) is 6g)

Dastarkhwan-e-Awadh, the book of Mughal Cuisine, describes Murgh Musallam as a royal dish, lending a certain majesty to the dastarkhwan. So the next time you order the luxuriously delicious Murgh Musallam from any restaurant, feel the glory of tasting a chicken dish worthy for the mightiest Mughal kings of the past centuries!

...Read Less

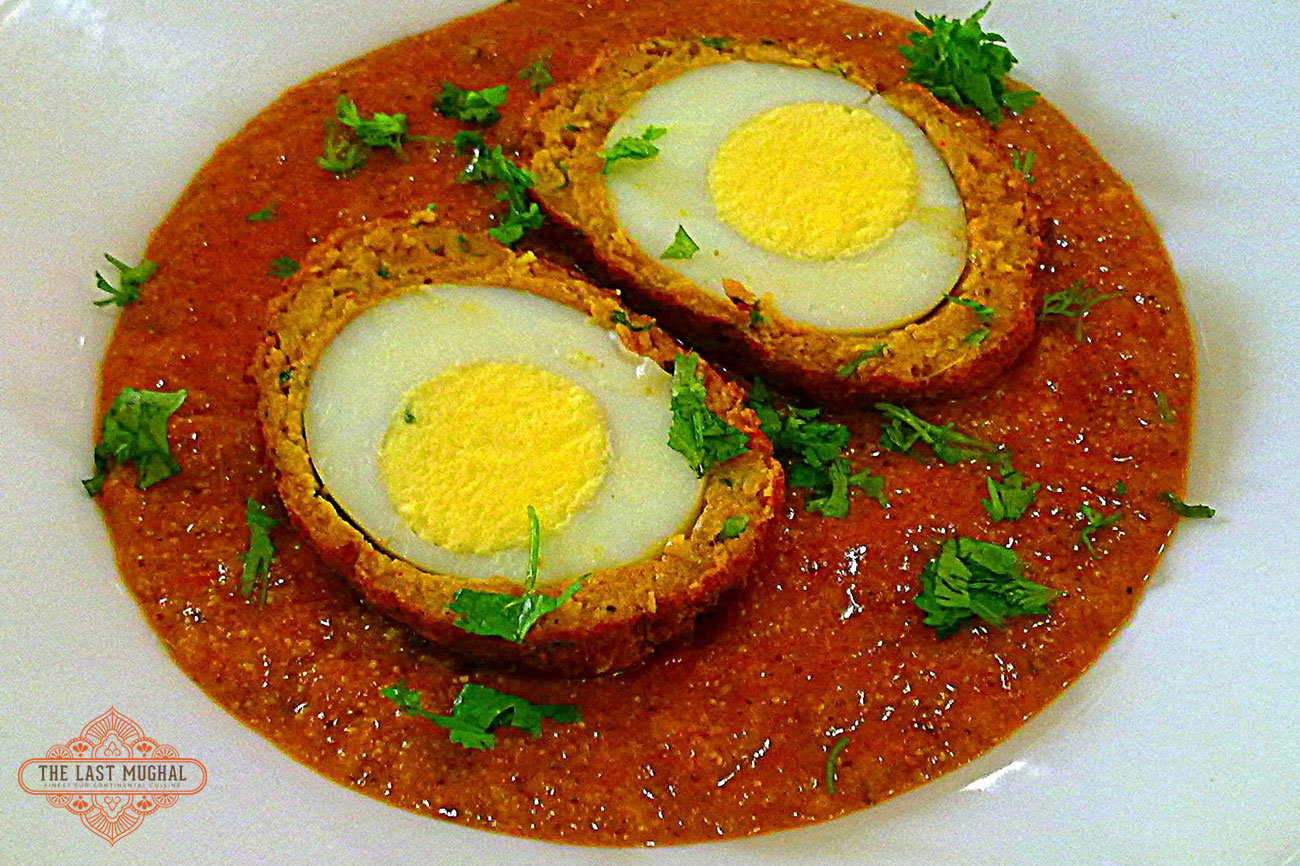

NARGISI KOFTA – THE MUGHAL SCOTCH EGG

A dish essentially marking its presence at various special occasions of the sub-continent is that of steaming hot meat-breaded eggs in a tantalizingly rich gravy, referred to as Nargisi Kofta. Alternately, either poached eggs or hard-boiled eggs may be used therein, depending upon whether you like the soft luscious yolk to ooze out for taste enhancement or you like it solid textured and wholesome.

Nargisi Koftas have a long, rather debatable history. Many food historians have associated the dish to be borrowed from the British Scoth Egg idea whilst others hold that it originated in the Mughal era and was replicated by the Britishers upon their visit to the Indian subcontinent.

Michelin-starred chef Graham Campbell holds that Scotch Eggs originated in Whitby, Yorkshire, England, in the 19th century, and were made with boiled eggs wrapped in minced pork, herbs and spices and deep fried whilst being served cold. However, executive chef of Royal Bengal Vijay Malhotra

A dish essentially marking its presence at various special occasions of the sub-continent is that of steaming hot meat-breaded eggs in a tantalizingly rich gravy, referred to as Nargisi Kofta. Alternately, either poached eggs or hard-boiled eggs may be used therein, depending upon whether you like the soft luscious yolk to ooze out for taste enhancement or you like it solid textured and wholesome.

Nargisi Koftas have a long, rather debatable history. Many food historians have associated the dish to be borrowed from the British Scoth Egg idea whilst others hold that it originated in the Mughal era and was replicated by the Britishers upon their visit to the Indian subcontinent.

Michelin-starred chef Graham Campbell holds that Scotch Eggs originated in Whitby, Yorkshire, England, in the 19th century, and were made with boiled eggs wrapped in minced pork, herbs and spices and deep fried whilst being served cold. However, executive chef of Royal Bengal Vijay Malhotra emphasizes that Nargisi kofta is a Mughlai dish that originated when Emperor Babur invaded India in the 15th century. According to 20th century food historian Alan Davidson, Nargisi Kofta emerged a result of an experiment by an adventurous khansama (cook) who took a hard-boiled egg, enclosed it in mutton mince and deep fried it, prior being added to the curry. He further states that once the English had tasted this curry, they fell in love and tried to recreate it. However, as curry preparation seemed to be a tedious task, they British replaced the gravy with hot sauce. Food historian Dr Annie Gray summarizes the debate by pointing out that the first printed reference to Scotch Eggs appeared in 1808 and by that time the British would have been pretty familiar with Nargisi Kofta from trading with and, later, colonizing India.

According to The Oxford Companion to Food, Nargisi Kofta is a popular sub continental dinner dish with the egg being generally wrapped inside meat mince and fried, then served in a brown, yoghurt-based gravy.

The name Nargisi Kofta comes from the flower named Nargis (narcissus), a winter flower with a yellow center and white petals around it just like a boiled egg. When you cut the Nargisi Kofta it resembles the blossoming Nargis flower.

In short, Nargisi Kofta is a delectable delicacy of the Mughal era, with scotch eggs served in a royal gravy, that made its taste felt even in the British regime.

NIHARI – THE BREAKFAST STAPLE OF THE MUGHALS

Nihari is a stew based dish, prepared by slow-cooking the meat along with the bone marrow (hence the name Nalli Nihari). It is one of the most loved traditional breakfasts of the Mughal era. Whereas Mughals had made a mark in the culinary history of Indian Subcontinent, one such prominent and decadent dish that originated and is still in galore across the globe is Nihari. As per historians, the origin of Nihari dates back to the 17th or 18th century as an off-shoot of the Indo-Persian influences in the food, that were brought in by the Mughals.

Nihari was conventionally cooked through the night for six to eight hours, to be served at sunrise. It followed a process of cooking meat (shanks) slowly, laden with as many as fifty spices. The method to the cook traditional Nihari was to seal the lid of the shab daig (a round, large pot) with flour glue to maintain and retain maximum heat and steam for slow cooking. The meat was braised and then left to simmer in the aromatic an

Nihari is a stew based dish, prepared by slow-cooking the meat along with the bone marrow (hence the name Nalli Nihari). It is one of the most loved traditional breakfasts of the Mughal era. Whereas Mughals had made a mark in the culinary history of Indian Subcontinent, one such prominent and decadent dish that originated and is still in galore across the globe is Nihari. As per historians, the origin of Nihari dates back to the 17th or 18th century as an off-shoot of the Indo-Persian influences in the food, that were brought in by the Mughals.

Nihari was conventionally cooked through the night for six to eight hours, to be served at sunrise. It followed a process of cooking meat (shanks) slowly, laden with as many as fifty spices. The method to the cook traditional Nihari was to seal the lid of the shab daig (a round, large pot) with flour glue to maintain and retain maximum heat and steam for slow cooking. The meat was braised and then left to simmer in the aromatic and delightfully spicy essence of masalas. This entire process helped the meat to absorb the aromatic masalas and make the meat melt in the mouth.

The word 'Nihari' originates from the Arabic word "Nahar" which means "morning". It was originally eaten by Nawabs in the Mughal Empire as a breakfast item after their morning prayers (Fajr). After a hearty breakfast of Nihari, the Nawabs would take a nap till afternoon, when they would wake up for afternoon prayers. As time passed, Nihari became a favorite of the masses and the Mughal army, who would consume the stew for its energy-boosting properties to wade through the harsh wintery-mornings. Traditionally, Nihari was prepared overnight for 6-8 hours, in large cauldrons for laborers, who were involved in construction of Mughal forts and palaces. It was served to them first thing in the morning, for boosting their energy levels for the hands-on tasks. The high protein meat allowed for a progressively slow increase in blood sugar and therefore resulted in decreased cravings through the day.

Distinguished author Sadiya Dehlvi describes the culinary evolution of Nihari as ‘While Delhi already enjoyed a hearty mélange of food yet the culinary refinement came with the Mughals. The rich Mughlai spread with its Persian nuances tempered with Indian tastes and flavors spelt magic’. Executive Sous-Chef of Delhi Pavillion, Chef Kusha Mathur explained the different variants of Nihari in the following words; ‘Delhi's Nihari, for instance, is more reddish-orange as compared to Awadh's lighter and slightly yellower variant. So, there is definitely a difference, the difference that persisted and evolved over the years’.

There is also a rather interesting culinary practice wherein a few kilos from each day's leftover Nihari is added to the next day's pot by traditional restaurants. This re-used portion of Nihari is called Taar and is known to add a unique and rich spicy flavor to the freshly cooked Nihari. There are some Nihari outlets that still boast of an unbroken 'taar', which can be traced back over a century!

Nihari was also used as a home remedy for common cold and fever by the noted hakims of the Mughal dynasty. Lauded for its medicinal properties and out-of-the-world flavors, the buttery and spicy Nihari is like magic in a pot that is best enjoyed with Khameeri Roti. Today, Nalli Nihari is part of almost every traditional sub-continental restaurant and no meat lover can resist the pull of this silky stew.

THE ‘BEWITCHING’ STORY BEHIND MUGHLAI RARA MEAT

There’s so much to learn about Mughal culinary history. Every recipe has a wonderful story behind its existence and how it came to be. The royal Mughal food that has many historical origins and whimsical tales attached, which lures the reader into getting a magical taste of the Emperors’ food. Mutton Rara recipe is one of the many curries loved by Asians and western countries alike. This spicy delicacy originates from the Mughals from central Asian province. Mutton Rara is a combination of minced meat and long meat pieces with a variety of spices. That makes is it must have a dish on special occasions.

Rara Gosht is a rich Mughlai dish which is said to have originated in the kitchen of Awadhi Nawabs. The fairytale associated with Rara Gosht is what makes it all the more fascinating and appealing to culinary enthusiasts. Legend says that the Chhotay Nawab of Awadh, and the Rajkumari of Jaipur were madly in love with each other and wished to be together but life had othe

There’s so much to learn about Mughal culinary history. Every recipe has a wonderful story behind its existence and how it came to be. The royal Mughal food that has many historical origins and whimsical tales attached, which lures the reader into getting a magical taste of the Emperors’ food. Mutton Rara recipe is one of the many curries loved by Asians and western countries alike. This spicy delicacy originates from the Mughals from central Asian province. Mutton Rara is a combination of minced meat and long meat pieces with a variety of spices. That makes is it must have a dish on special occasions.

Rara Gosht is a rich Mughlai dish which is said to have originated in the kitchen of Awadhi Nawabs. The fairytale associated with Rara Gosht is what makes it all the more fascinating and appealing to culinary enthusiasts. Legend says that the Chhotay Nawab of Awadh, and the Rajkumari of Jaipur were madly in love with each other and wished to be together but life had other plans. They had a clandestine love affair and their families found out. The princess was whisked away to a fortress surrounded by deep waters and guarded by an evil witch. The prince yearned for his ladylove, but was unable to get in. The witch was clever and unforgiving, but she had one weakness: mutton. The prince called down the finest khansamas of his great empire to create a mutton dish so delicious that it would render the witch powerless. And so the dish was prepared near the moat of the bewitched castle. Cooked slowly and patiently in whole spices including black cardamom, green cardamom, bay leaves, cinnamon sticks, cloves, whole black peppercorns, star anise, cumin seeds and Kashmiri red chillis, the royal chefs cooked and stirred and as the masalas roasted, the deep sensuous aromas arose and wafted through to the fortress. The meat simmered and began to tenderize, and the witch could not control herself and magically transported the pot to her chamber. She loved the preparation so much, that she actually gave the Rajkumari away to the Chhota Nawab and blessed them with eternal happiness. The magnanimous prince named the magical preparation after the witch, whose name was Rara, hence Mutton Rara.

This royal and extravagant dish is a double whammy of mutton boti (goat meat pieces) and Qeema (goat mince) which needs to be made with a lot of love and a little bit of effort. It is deliciously spicy and rich in appearance. When consumed in the right quantity, Rara meat is highly nutritious for the body as goat meat contains a good amount of protein with amino acids and a rich amount of zinc, iron, and selenium. Vitamins A, B, and D are also plentiful in meat. Hence, eating Rara Meat will give you taste, nutrition, majesty and fantasy, all in one experience!

...Read Less

PANCHMEL DAL – THE ROYAL MARRIAGE OF PULSES

In the nascent Indian subcontinent, the reinforcement of the dum pukht technique (slow cooking in steam) raised the stature of dal in the royal menu. One such dal that rose to prominence in the royal kitchens is the panchmel dal (also referred to as panchratna dal). Little can be said with substantiation about the exact origin of this lentil preparation. However, it is assumed that the panchmel dal first came into limelight in the Mewar Gharana. This simple, nutritious and subtly flavoured mix of five lentils – moong dal, chana dal, toor dal, masoor dal and urad dal – panchmel dal went beautifully with the use of curd and buttermilk. Such was the importance of this tomato-less lentil that it was one of Jodha Bai’s favorite dishes that she introduced to Mughal e Azam Akbar, upon marriage.

Although the Mughal kitchen was predominantly non-vegetarian yet interestingly, Akbar was a vegetarian three times a week. Therefore, it became such a hit with Mughal ro

In the nascent Indian subcontinent, the reinforcement of the dum pukht technique (slow cooking in steam) raised the stature of dal in the royal menu. One such dal that rose to prominence in the royal kitchens is the panchmel dal (also referred to as panchratna dal). Little can be said with substantiation about the exact origin of this lentil preparation. However, it is assumed that the panchmel dal first came into limelight in the Mewar Gharana. This simple, nutritious and subtly flavoured mix of five lentils – moong dal, chana dal, toor dal, masoor dal and urad dal – panchmel dal went beautifully with the use of curd and buttermilk. Such was the importance of this tomato-less lentil that it was one of Jodha Bai’s favorite dishes that she introduced to Mughal e Azam Akbar, upon marriage.

Although the Mughal kitchen was predominantly non-vegetarian yet interestingly, Akbar was a vegetarian three times a week. Therefore, it became such a hit with Mughal royalty that by the time Shah Jahan took over the empire, the court had its own shahi panchmel dal recipe! It also held a place of pride on the dining table of Aurangzeb who, being a strict vegetarian, ancied the dish more than the roast meat dishes that his forefathers were so fond of.

Food historians also believe that the panchmel dal may have been born out of the obligation to create a different tasting dal for the royal meal every day, by varying the combinations of dal and the tempering to ensure that the dal tasted different every time! The dal, while being full of taste, did allow immense scope for the khansamas to work around. This may explain why even after all these years, tomato isn’t a part of the recipe that uses subtle flavour spices and relies heavily on clarified butter or ghee to do the trick.

...Read Less